28 December 2011

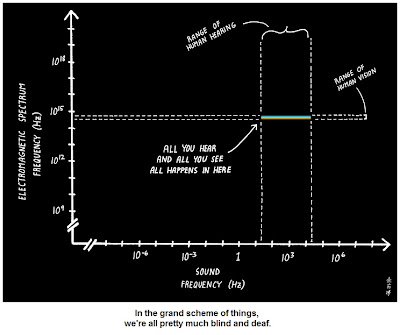

A little perspective on human perception

It’s good to occasionally have a reality check to temper our hubris. But I think it’s only fair to acknowledge that our technology – created through the application of our unique powers of reason and distinctly human ingenuity – allows us to see and hear far beyond our natural limits. Telescopes, microscopes, spectrometers, microphones and stethoscopes are inventions that our species can be rightfully proud of.

HT: PZ Myers

28.12.11

23 December 2011

I don’t care what he says, I’m wishing y’all a Merry Christmas

Our facially hirsute friend has got one thing right though – wishing others a Merry Christmas is definitely worse than fornicating. Offering season’s greetings to someone never gave me a mind-blowing, buttock-clenching, gasp-inducing orgasm. But I’m normal and boring like that.

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays, you alcohol-swilling fornicators!

HT: Maryam Namazie

24.12.11

22 December 2011

Blackford on the UN’s new stance regarding ‘defamation of religion’

The UN, to paraphrase Churchill, can always be counted on to do the right thing – after it’s tried everything else. For the first time since 1998, the UN General Assembly didn’t qualify its latest call for religious tolerance with the expectation that states ban all forms of expression perceived to be critical or insulting towards religion.

No prizes for guessing which brand of sky-fairyism was largely behind the anti-religious defamation ban: of all the major religions, Islam is arguably the only one that has state-sanctioned anti-blasphemy tendencies that often manifest in violent, murderous ways. Until recently, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), which comprises 57 Muslim-majority countries, was successful in pushing through annual UN resolutions on “combating defamation of religions”. But the OIC’s decade-long winning streak has finally been broken.

Russell Blackford’s new book Freedom of Religion and the Secular State explores the relevant issues of freedom of speech and freedom of religion in depth. Blackford wrote the following comments on his blog, which touch on the salient aspects of the UN’s position, past and present, regarding religious defamation:

Any ideology, religious or otherwise, that requires force and coercion to propagate reveals itself to be insecure, flawed, and tyrannical. You have to threaten, torture, jail and execute people to make them accept the validity of absurd ideas. True and good ideas on the other hand are self-evident to all reasonable people.

22.12.11

No prizes for guessing which brand of sky-fairyism was largely behind the anti-religious defamation ban: of all the major religions, Islam is arguably the only one that has state-sanctioned anti-blasphemy tendencies that often manifest in violent, murderous ways. Until recently, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), which comprises 57 Muslim-majority countries, was successful in pushing through annual UN resolutions on “combating defamation of religions”. But the OIC’s decade-long winning streak has finally been broken.

Russell Blackford’s new book Freedom of Religion and the Secular State explores the relevant issues of freedom of speech and freedom of religion in depth. Blackford wrote the following comments on his blog, which touch on the salient aspects of the UN’s position, past and present, regarding religious defamation:

It is one thing for the UN to condemn actions to provoke inter-religious hatred. No one wants to see the world’s societies riven with hatred, though it is worth remembering that much of the hatred comes from religious conservatives who refuse to tolerate sexual freedom (especially that of women), female emancipation, and any expressions of erotic love outside of heterosexual monogamy. Even in Western societies we see this in the emotive opposition to abortion rights and same-sex marriage. It’s another thing to become so focused on this issue that important kinds of speech are stigmatised and even prohibited. There is a public interest in scrutiny of religion, and it should be a fair target for criticism, denunciation, or satire.

At any rate, we should always err, if err we must, on the side of freedom of speech. Whatever lines are drawn in the area should allow bold speech that might offend – and this includes various forms of anti-religious criticism and satire. Such a liberal attitude to speech might permit some ugly speech, but the long-term effect would be to reinforce a valuable lesson: ideologically opposed groups of whatever kind – religious, political, or philosophical – must make their own way, enduring criticism, and even satire, from their opponents, without asking the state to interfere.

Any ideology, religious or otherwise, that requires force and coercion to propagate reveals itself to be insecure, flawed, and tyrannical. You have to threaten, torture, jail and execute people to make them accept the validity of absurd ideas. True and good ideas on the other hand are self-evident to all reasonable people.

22.12.11

20 December 2011

Heaven is like North Korea

So the death of a vile man follows soon after the death of a good one. In his capacity as a journalist, Christopher Hitchens had visited North Korea and written about the failed state and its now deceased dictator, Kim Jong Il. In a Slate article last year, Hitchens wrote:

Far from being the poster child for evil godlessness, North Korea is inherently religious: its founder is worshipped as a divine being, while miracles and portents intending to legitimate the totalitarian rule of the Kim dynasty are propagated just like the myths surrounding Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha and every other religious figure. Furthermore, as Hitchens observed in the video below, the constant adulation of the Great Leader bears a disturbing resemblance to what Heaven is supposed to be like: a place where billions of souls offer up everlasting praise to their lord and master.

ADDENDUM: Here's Hitchens describing his experience in North Korea, and explaining how religious its society actually is.

20.12.11

Unlike previous racist dictatorships, the North Korean one has actually succeeded in producing a sort of new species. Starving and stunted dwarves, living in the dark, kept in perpetual ignorance and fear, brainwashed into the hatred of others, regimented and coerced and inculcated with a death cult.

Far from being the poster child for evil godlessness, North Korea is inherently religious: its founder is worshipped as a divine being, while miracles and portents intending to legitimate the totalitarian rule of the Kim dynasty are propagated just like the myths surrounding Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha and every other religious figure. Furthermore, as Hitchens observed in the video below, the constant adulation of the Great Leader bears a disturbing resemblance to what Heaven is supposed to be like: a place where billions of souls offer up everlasting praise to their lord and master.

I couldn’t picture [Heaven]… but I’ve seen the nearest approximation to it, which is North Korea, where it is the only duty and job and right for a citizen to eternally praise the Divine Leader and his Divine Father. […] North Korea is only one short of a Trinity.

ADDENDUM: Here's Hitchens describing his experience in North Korea, and explaining how religious its society actually is.

20.12.11

17 December 2011

Dawkins’s eulogy to Hitchens pulls no punches

Christopher Hitchens is dead. This isn’t going to be the post where I express what the Hitch and his work mean to me. Right now there are too many scattered thoughts that I have yet to gather into a coherent tribute to one of my intellectual and ethical heroes. Until I find the time to sit down and do said gathering, this will serve as a stop-gap.

Jerry Coyne posted this excerpt from Richard Dawkins’s eulogy to his fallen atheist comrade. For all its eloquence, it has the air of an undisguised “fuck you” to the religious. And appropriately so.

[Hitchens] inspired, energised and encouraged us. He had us cheering him on almost daily. He even begat a new word – the hitchslap. It wasn’t just his intellect we admired: it was also his pugnacity, his spirit, his refusal to countenance ignoble compromise, his forthrightness, his indomitable spirit, his brutal honesty.

And in the very way he looked his illness in the eye, he embodied one part of the case against religion. Leave it to the religious to mewl and whimper at the feet of an imaginary deity in their fear of death; leave it to them to spend their lives in denial of its reality. Hitch looked it squarely in the eye: not denying it, not giving in to it, but facing up to it squarely and honestly and with a courage that inspires us all.

Before his illness, it was as an erudite author, essayist and sparkling, devastating speaker that this valiant horseman led the charge against the follies and lies of religion. During his illness he added another weapon to his armoury and ours – perhaps the most formidable and powerful weapon of all: his very character became an outstanding and unmistakable symbol of the honesty and dignity of atheism, as well as of the worth and dignity of the human being when not debased by the infantile babblings of religion.

Every day of his declining life he demonstrated the falsehood of that most squalid of Christian lies: that there are no atheists in foxholes. Hitch was in a foxhole, and he dealt with it with a courage, an honesty and a dignity that any of us would be, and should be, proud to be able to muster. And in the process, he showed himself to be even more deserving of our admiration, respect, and love.

Farewell, great voice. Great voice of reason, of humanity, of humour. Great voice against cant, against hypocrisy, against obscurantism and pretension, against all tyrants including God.

18.12.11

06 December 2011

On wearing a uniform (that isn’t a uniform)

Fashion is primarily a visual affair. While I can only speak for myself, I find a lot of fashion writing to be akin to postmodernist twaddle: pretentious in its depiction of the superficial as profound and in its forced, obscure intellectualism, stale with its mix-n-match pastiche of trite phrases, clichés and silly neologisms (seriously, ‘murse’?). I would much rather look at pictures of interesting clothes that haven’t been mediated through fashionspeak. This is why I prefer fashion blogs like The Sartorialist that focus on the imagery of clothing and the people wearing it, unlike other more chatty blogs that run often inane commentary alongside the pictures.

But on rare occasions, I come across fashion writing that doesn’t try to pass itself off as deconstructionist prose. Where the writing is honest, intelligible and even humble, if that word could be applied to something as narcissistic as fashion. The autumn/winter 2011 issue of menswear magazine Dapper Dan has such writing, in an article by Angelo Flaccavento (‘Long Live the Immaterial’). Flaccavento is a proponent of ‘uniform dressing’, though he doesn’t mean it in the institutional sense (military, corporate, sports etc). I’ll let the man himself explain.

Flaccavento is my kind of sartorial ideologue. His ‘uniform that is not a uniform’ describes my dress sense. I almost always wear the following: a classic hat, whether a felt fedora, wool fisherman’s cap or straw sunhat; leather lace-up boots or plain canvas slip-ons; a tailored two-button jacket; ankle-length pants with little to no break; button-up shirts, plain or vertically striped (and always tucked in). It has taken me about 4 years of experimentation to finally settle on this selection of garments that constitute my Flaccaventonian uniform.

Here are some of the key influences on my style (click on the images to enlarge them):

Lewis Hine’s early 20th century photos of European migrants, working class men and child labourers.

Winslow Homer’s 19th century paintings of rural Americans.

The period costumes in films like Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard and Claude Berri’s Jean de Florette.

The picture below is from Manon des Sources, the sequel to Jean de Florette. The woman’s clothes display the colours and textures that I’m fond of.

This is Flaccavento’s dressing manifesto. I would happily sign up to it.

6.12.11

But on rare occasions, I come across fashion writing that doesn’t try to pass itself off as deconstructionist prose. Where the writing is honest, intelligible and even humble, if that word could be applied to something as narcissistic as fashion. The autumn/winter 2011 issue of menswear magazine Dapper Dan has such writing, in an article by Angelo Flaccavento (‘Long Live the Immaterial’). Flaccavento is a proponent of ‘uniform dressing’, though he doesn’t mean it in the institutional sense (military, corporate, sports etc). I’ll let the man himself explain.

[W]hat people do with their own wardrobes and lives is none of my business. Prescriptions are proscriptive and I am no teacher. Still, I’d like to humbly suggest another way: uniform dressing. I am not talking about military gear, brass buttons and epaulettes, though I am wildly fascinated by them. I am referring to a formulaic approach to dressing up: choosing what’s best for you and sticking with it. Abandoning the perils of the fashionable for the cozy retreat of the familiar and tasteful. Playing it safe, some might say. But it takes time, care and attention to create a uniform that is not a uniform. Along the way, you will discover the liberating joy of having no options. All of this can be done without forsaking the deep pleasures of dress-up.

Flaccavento is my kind of sartorial ideologue. His ‘uniform that is not a uniform’ describes my dress sense. I almost always wear the following: a classic hat, whether a felt fedora, wool fisherman’s cap or straw sunhat; leather lace-up boots or plain canvas slip-ons; a tailored two-button jacket; ankle-length pants with little to no break; button-up shirts, plain or vertically striped (and always tucked in). It has taken me about 4 years of experimentation to finally settle on this selection of garments that constitute my Flaccaventonian uniform.

Here are some of the key influences on my style (click on the images to enlarge them):

Lewis Hine’s early 20th century photos of European migrants, working class men and child labourers.

Winslow Homer’s 19th century paintings of rural Americans.

The period costumes in films like Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard and Claude Berri’s Jean de Florette.

The picture below is from Manon des Sources, the sequel to Jean de Florette. The woman’s clothes display the colours and textures that I’m fond of.

This is Flaccavento’s dressing manifesto. I would happily sign up to it.

1. Be light. Don’t turn your opinion of fashion into a declaration of war. Maintaining a uniform is your choice, not a dogma.

2. Know that you are in good company. Coco Chanel, Diana Vreeland, Gio Ponti and Beau Brummell all excelled in the practice. But don’t use it as an excuse to look down on others. Refrain from judging.

3. Look at yourself in the mirror, thoroughly and severely. Consider your pros and cons, and decide what to highlight. It can be everything. Sometimes cons are more charming than pros; a prominent belly can be more sensational than a six-pack. Trust your instincts, and the uniform will begin to feel natural.

4. Trust in Dieter Rams: “Less, but better.” Edit down to the bare essentials, plus, perhaps, a tiny bit more. You should be able to get ready in a flash with a thoughtful, quick edit. Likewise, never plan an outfit in advance; the result will be rigid. A little mistake here and there feels lively.

5. Be modular: you will augment your sartorial possibilities in a logical, efficient way. If you can mix and match, your wardrobe will expand virtually without taking up vital space.

6. Choose your uniform according to the idea of yourself you have in mind. Let the immaterial shape your material expression of your persona, without restrictions or boundaries. Stripes and mismatched patterns can be to you what solid black or clerk-like grey is to others. That’s how the game works.

7. Ignore what people say. Wear a suit to the grocery store, if you wish. Clothes should be an expression of your inner self, but they should also display courtesy. Dressing appropriately is a gesture of kindness, for oneself and for others.

8. Look at what’s happening in fashion. Be critical, but look. Then adopt and adapt, or you’ll turn into a grumpy old statue covered in dust.

9. Evolve, avoiding dogmatism and orthodoxy. You’re not the same person from day to day. Your uniform should change accordingly.

10. Defy expectations. Don’t let the uniform take over, and don’t allow yourself to be identified by your uniform. Break it up once in a while. Be a prankster. Remember: situationism rules.

11. Hey, they’re just clothes: you’ll get tired of them sooner than you think.

6.12.11

02 December 2011

Pinker on what science is all about

I’m making my way through Michael Shermer’s The Believing Brain at the moment, so Steven Pinker’s latest book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, is still languishing on my ‘to read’ list. I’m aware that it’s a BIG book, but Jerry Coyne has started reading it and his thoughts on its, uh, bigness is actually scaring me a little. It’s most likely going to take me a good part of early 2012 to finish it. But Pinker is a splendid writer with a knack for spinning a good (and in this case, often grisly) yarn out of all the reams of data and graphs his books typically contain.

Coyne selects the following paragraph from Better Angels as a standout for the way it articulates Pinker’s views on science, which concur with Coyne’s.

After reading that, how can any reasonable person still think that scientists are arrogant, cocksure know-it-alls? The scientific enterprise is arguably the most humbling experience one could have. Scientists get it wrong many, many times before they find the correct answers. And they’re constantly going over each other’s work with a magnifying glass, just hoping to find errors or unsubstantiated claims to gleefully point out. I’m no scientist, but I imagine that having one’s research subjected to such intense scrutiny by so many experts leaves little opportunity for inflated egos.

Notice that Pinker makes a value judgment when he writes that science is “a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge”, and that it’s not just the “particular methods or institutions of science but its value system” that give it its unique powers of discovery and illumination. Science is a moral undertaking. When people dedicate themselves to science, they are also declaring their commitment to moral values like honesty, humility and integrity. When they abandon any of these values, they cease doing science.

3.12.11

Coyne selects the following paragraph from Better Angels as a standout for the way it articulates Pinker’s views on science, which concur with Coyne’s.

(p. 181) Though we cannot logically prove anything about the physical world, we are entitled to have confidence in certain beliefs about it. The application of reason and observation to discover tentative generalizations about the world is what we call science. The progress of science with its dazzling success at explaining and manipulating the world, shows that knowledge of the universe is possible, albeit always probabilistic and subject to revision. Science is thus a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge—not the particular methods or institutions of science but its value system, namely to seek to explain the world, to evaluate candidate explanations objectively, and to be cognizant of the tentativeness and uncertainty of our understanding at any time.

After reading that, how can any reasonable person still think that scientists are arrogant, cocksure know-it-alls? The scientific enterprise is arguably the most humbling experience one could have. Scientists get it wrong many, many times before they find the correct answers. And they’re constantly going over each other’s work with a magnifying glass, just hoping to find errors or unsubstantiated claims to gleefully point out. I’m no scientist, but I imagine that having one’s research subjected to such intense scrutiny by so many experts leaves little opportunity for inflated egos.

Notice that Pinker makes a value judgment when he writes that science is “a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge”, and that it’s not just the “particular methods or institutions of science but its value system” that give it its unique powers of discovery and illumination. Science is a moral undertaking. When people dedicate themselves to science, they are also declaring their commitment to moral values like honesty, humility and integrity. When they abandon any of these values, they cease doing science.

3.12.11

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)