28 December 2011

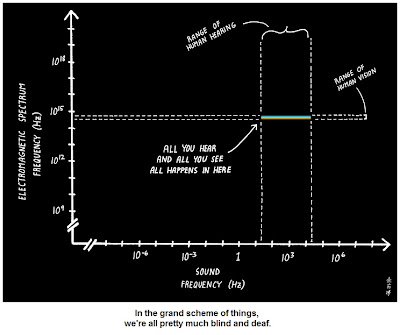

A little perspective on human perception

It’s good to occasionally have a reality check to temper our hubris. But I think it’s only fair to acknowledge that our technology – created through the application of our unique powers of reason and distinctly human ingenuity – allows us to see and hear far beyond our natural limits. Telescopes, microscopes, spectrometers, microphones and stethoscopes are inventions that our species can be rightfully proud of.

HT: PZ Myers

28.12.11

23 December 2011

I don’t care what he says, I’m wishing y’all a Merry Christmas

Our facially hirsute friend has got one thing right though – wishing others a Merry Christmas is definitely worse than fornicating. Offering season’s greetings to someone never gave me a mind-blowing, buttock-clenching, gasp-inducing orgasm. But I’m normal and boring like that.

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays, you alcohol-swilling fornicators!

HT: Maryam Namazie

24.12.11

22 December 2011

Blackford on the UN’s new stance regarding ‘defamation of religion’

The UN, to paraphrase Churchill, can always be counted on to do the right thing – after it’s tried everything else. For the first time since 1998, the UN General Assembly didn’t qualify its latest call for religious tolerance with the expectation that states ban all forms of expression perceived to be critical or insulting towards religion.

No prizes for guessing which brand of sky-fairyism was largely behind the anti-religious defamation ban: of all the major religions, Islam is arguably the only one that has state-sanctioned anti-blasphemy tendencies that often manifest in violent, murderous ways. Until recently, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), which comprises 57 Muslim-majority countries, was successful in pushing through annual UN resolutions on “combating defamation of religions”. But the OIC’s decade-long winning streak has finally been broken.

Russell Blackford’s new book Freedom of Religion and the Secular State explores the relevant issues of freedom of speech and freedom of religion in depth. Blackford wrote the following comments on his blog, which touch on the salient aspects of the UN’s position, past and present, regarding religious defamation:

Any ideology, religious or otherwise, that requires force and coercion to propagate reveals itself to be insecure, flawed, and tyrannical. You have to threaten, torture, jail and execute people to make them accept the validity of absurd ideas. True and good ideas on the other hand are self-evident to all reasonable people.

22.12.11

No prizes for guessing which brand of sky-fairyism was largely behind the anti-religious defamation ban: of all the major religions, Islam is arguably the only one that has state-sanctioned anti-blasphemy tendencies that often manifest in violent, murderous ways. Until recently, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC), which comprises 57 Muslim-majority countries, was successful in pushing through annual UN resolutions on “combating defamation of religions”. But the OIC’s decade-long winning streak has finally been broken.

Russell Blackford’s new book Freedom of Religion and the Secular State explores the relevant issues of freedom of speech and freedom of religion in depth. Blackford wrote the following comments on his blog, which touch on the salient aspects of the UN’s position, past and present, regarding religious defamation:

It is one thing for the UN to condemn actions to provoke inter-religious hatred. No one wants to see the world’s societies riven with hatred, though it is worth remembering that much of the hatred comes from religious conservatives who refuse to tolerate sexual freedom (especially that of women), female emancipation, and any expressions of erotic love outside of heterosexual monogamy. Even in Western societies we see this in the emotive opposition to abortion rights and same-sex marriage. It’s another thing to become so focused on this issue that important kinds of speech are stigmatised and even prohibited. There is a public interest in scrutiny of religion, and it should be a fair target for criticism, denunciation, or satire.

At any rate, we should always err, if err we must, on the side of freedom of speech. Whatever lines are drawn in the area should allow bold speech that might offend – and this includes various forms of anti-religious criticism and satire. Such a liberal attitude to speech might permit some ugly speech, but the long-term effect would be to reinforce a valuable lesson: ideologically opposed groups of whatever kind – religious, political, or philosophical – must make their own way, enduring criticism, and even satire, from their opponents, without asking the state to interfere.

Any ideology, religious or otherwise, that requires force and coercion to propagate reveals itself to be insecure, flawed, and tyrannical. You have to threaten, torture, jail and execute people to make them accept the validity of absurd ideas. True and good ideas on the other hand are self-evident to all reasonable people.

22.12.11

20 December 2011

Heaven is like North Korea

So the death of a vile man follows soon after the death of a good one. In his capacity as a journalist, Christopher Hitchens had visited North Korea and written about the failed state and its now deceased dictator, Kim Jong Il. In a Slate article last year, Hitchens wrote:

Far from being the poster child for evil godlessness, North Korea is inherently religious: its founder is worshipped as a divine being, while miracles and portents intending to legitimate the totalitarian rule of the Kim dynasty are propagated just like the myths surrounding Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha and every other religious figure. Furthermore, as Hitchens observed in the video below, the constant adulation of the Great Leader bears a disturbing resemblance to what Heaven is supposed to be like: a place where billions of souls offer up everlasting praise to their lord and master.

ADDENDUM: Here's Hitchens describing his experience in North Korea, and explaining how religious its society actually is.

20.12.11

Unlike previous racist dictatorships, the North Korean one has actually succeeded in producing a sort of new species. Starving and stunted dwarves, living in the dark, kept in perpetual ignorance and fear, brainwashed into the hatred of others, regimented and coerced and inculcated with a death cult.

Far from being the poster child for evil godlessness, North Korea is inherently religious: its founder is worshipped as a divine being, while miracles and portents intending to legitimate the totalitarian rule of the Kim dynasty are propagated just like the myths surrounding Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha and every other religious figure. Furthermore, as Hitchens observed in the video below, the constant adulation of the Great Leader bears a disturbing resemblance to what Heaven is supposed to be like: a place where billions of souls offer up everlasting praise to their lord and master.

I couldn’t picture [Heaven]… but I’ve seen the nearest approximation to it, which is North Korea, where it is the only duty and job and right for a citizen to eternally praise the Divine Leader and his Divine Father. […] North Korea is only one short of a Trinity.

ADDENDUM: Here's Hitchens describing his experience in North Korea, and explaining how religious its society actually is.

20.12.11

17 December 2011

Dawkins’s eulogy to Hitchens pulls no punches

Christopher Hitchens is dead. This isn’t going to be the post where I express what the Hitch and his work mean to me. Right now there are too many scattered thoughts that I have yet to gather into a coherent tribute to one of my intellectual and ethical heroes. Until I find the time to sit down and do said gathering, this will serve as a stop-gap.

Jerry Coyne posted this excerpt from Richard Dawkins’s eulogy to his fallen atheist comrade. For all its eloquence, it has the air of an undisguised “fuck you” to the religious. And appropriately so.

[Hitchens] inspired, energised and encouraged us. He had us cheering him on almost daily. He even begat a new word – the hitchslap. It wasn’t just his intellect we admired: it was also his pugnacity, his spirit, his refusal to countenance ignoble compromise, his forthrightness, his indomitable spirit, his brutal honesty.

And in the very way he looked his illness in the eye, he embodied one part of the case against religion. Leave it to the religious to mewl and whimper at the feet of an imaginary deity in their fear of death; leave it to them to spend their lives in denial of its reality. Hitch looked it squarely in the eye: not denying it, not giving in to it, but facing up to it squarely and honestly and with a courage that inspires us all.

Before his illness, it was as an erudite author, essayist and sparkling, devastating speaker that this valiant horseman led the charge against the follies and lies of religion. During his illness he added another weapon to his armoury and ours – perhaps the most formidable and powerful weapon of all: his very character became an outstanding and unmistakable symbol of the honesty and dignity of atheism, as well as of the worth and dignity of the human being when not debased by the infantile babblings of religion.

Every day of his declining life he demonstrated the falsehood of that most squalid of Christian lies: that there are no atheists in foxholes. Hitch was in a foxhole, and he dealt with it with a courage, an honesty and a dignity that any of us would be, and should be, proud to be able to muster. And in the process, he showed himself to be even more deserving of our admiration, respect, and love.

Farewell, great voice. Great voice of reason, of humanity, of humour. Great voice against cant, against hypocrisy, against obscurantism and pretension, against all tyrants including God.

18.12.11

06 December 2011

On wearing a uniform (that isn’t a uniform)

Fashion is primarily a visual affair. While I can only speak for myself, I find a lot of fashion writing to be akin to postmodernist twaddle: pretentious in its depiction of the superficial as profound and in its forced, obscure intellectualism, stale with its mix-n-match pastiche of trite phrases, clichés and silly neologisms (seriously, ‘murse’?). I would much rather look at pictures of interesting clothes that haven’t been mediated through fashionspeak. This is why I prefer fashion blogs like The Sartorialist that focus on the imagery of clothing and the people wearing it, unlike other more chatty blogs that run often inane commentary alongside the pictures.

But on rare occasions, I come across fashion writing that doesn’t try to pass itself off as deconstructionist prose. Where the writing is honest, intelligible and even humble, if that word could be applied to something as narcissistic as fashion. The autumn/winter 2011 issue of menswear magazine Dapper Dan has such writing, in an article by Angelo Flaccavento (‘Long Live the Immaterial’). Flaccavento is a proponent of ‘uniform dressing’, though he doesn’t mean it in the institutional sense (military, corporate, sports etc). I’ll let the man himself explain.

Flaccavento is my kind of sartorial ideologue. His ‘uniform that is not a uniform’ describes my dress sense. I almost always wear the following: a classic hat, whether a felt fedora, wool fisherman’s cap or straw sunhat; leather lace-up boots or plain canvas slip-ons; a tailored two-button jacket; ankle-length pants with little to no break; button-up shirts, plain or vertically striped (and always tucked in). It has taken me about 4 years of experimentation to finally settle on this selection of garments that constitute my Flaccaventonian uniform.

Here are some of the key influences on my style (click on the images to enlarge them):

Lewis Hine’s early 20th century photos of European migrants, working class men and child labourers.

Winslow Homer’s 19th century paintings of rural Americans.

The period costumes in films like Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard and Claude Berri’s Jean de Florette.

The picture below is from Manon des Sources, the sequel to Jean de Florette. The woman’s clothes display the colours and textures that I’m fond of.

This is Flaccavento’s dressing manifesto. I would happily sign up to it.

6.12.11

But on rare occasions, I come across fashion writing that doesn’t try to pass itself off as deconstructionist prose. Where the writing is honest, intelligible and even humble, if that word could be applied to something as narcissistic as fashion. The autumn/winter 2011 issue of menswear magazine Dapper Dan has such writing, in an article by Angelo Flaccavento (‘Long Live the Immaterial’). Flaccavento is a proponent of ‘uniform dressing’, though he doesn’t mean it in the institutional sense (military, corporate, sports etc). I’ll let the man himself explain.

[W]hat people do with their own wardrobes and lives is none of my business. Prescriptions are proscriptive and I am no teacher. Still, I’d like to humbly suggest another way: uniform dressing. I am not talking about military gear, brass buttons and epaulettes, though I am wildly fascinated by them. I am referring to a formulaic approach to dressing up: choosing what’s best for you and sticking with it. Abandoning the perils of the fashionable for the cozy retreat of the familiar and tasteful. Playing it safe, some might say. But it takes time, care and attention to create a uniform that is not a uniform. Along the way, you will discover the liberating joy of having no options. All of this can be done without forsaking the deep pleasures of dress-up.

Flaccavento is my kind of sartorial ideologue. His ‘uniform that is not a uniform’ describes my dress sense. I almost always wear the following: a classic hat, whether a felt fedora, wool fisherman’s cap or straw sunhat; leather lace-up boots or plain canvas slip-ons; a tailored two-button jacket; ankle-length pants with little to no break; button-up shirts, plain or vertically striped (and always tucked in). It has taken me about 4 years of experimentation to finally settle on this selection of garments that constitute my Flaccaventonian uniform.

Here are some of the key influences on my style (click on the images to enlarge them):

Lewis Hine’s early 20th century photos of European migrants, working class men and child labourers.

Winslow Homer’s 19th century paintings of rural Americans.

The period costumes in films like Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard and Claude Berri’s Jean de Florette.

The picture below is from Manon des Sources, the sequel to Jean de Florette. The woman’s clothes display the colours and textures that I’m fond of.

This is Flaccavento’s dressing manifesto. I would happily sign up to it.

1. Be light. Don’t turn your opinion of fashion into a declaration of war. Maintaining a uniform is your choice, not a dogma.

2. Know that you are in good company. Coco Chanel, Diana Vreeland, Gio Ponti and Beau Brummell all excelled in the practice. But don’t use it as an excuse to look down on others. Refrain from judging.

3. Look at yourself in the mirror, thoroughly and severely. Consider your pros and cons, and decide what to highlight. It can be everything. Sometimes cons are more charming than pros; a prominent belly can be more sensational than a six-pack. Trust your instincts, and the uniform will begin to feel natural.

4. Trust in Dieter Rams: “Less, but better.” Edit down to the bare essentials, plus, perhaps, a tiny bit more. You should be able to get ready in a flash with a thoughtful, quick edit. Likewise, never plan an outfit in advance; the result will be rigid. A little mistake here and there feels lively.

5. Be modular: you will augment your sartorial possibilities in a logical, efficient way. If you can mix and match, your wardrobe will expand virtually without taking up vital space.

6. Choose your uniform according to the idea of yourself you have in mind. Let the immaterial shape your material expression of your persona, without restrictions or boundaries. Stripes and mismatched patterns can be to you what solid black or clerk-like grey is to others. That’s how the game works.

7. Ignore what people say. Wear a suit to the grocery store, if you wish. Clothes should be an expression of your inner self, but they should also display courtesy. Dressing appropriately is a gesture of kindness, for oneself and for others.

8. Look at what’s happening in fashion. Be critical, but look. Then adopt and adapt, or you’ll turn into a grumpy old statue covered in dust.

9. Evolve, avoiding dogmatism and orthodoxy. You’re not the same person from day to day. Your uniform should change accordingly.

10. Defy expectations. Don’t let the uniform take over, and don’t allow yourself to be identified by your uniform. Break it up once in a while. Be a prankster. Remember: situationism rules.

11. Hey, they’re just clothes: you’ll get tired of them sooner than you think.

6.12.11

02 December 2011

Pinker on what science is all about

I’m making my way through Michael Shermer’s The Believing Brain at the moment, so Steven Pinker’s latest book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, is still languishing on my ‘to read’ list. I’m aware that it’s a BIG book, but Jerry Coyne has started reading it and his thoughts on its, uh, bigness is actually scaring me a little. It’s most likely going to take me a good part of early 2012 to finish it. But Pinker is a splendid writer with a knack for spinning a good (and in this case, often grisly) yarn out of all the reams of data and graphs his books typically contain.

Coyne selects the following paragraph from Better Angels as a standout for the way it articulates Pinker’s views on science, which concur with Coyne’s.

After reading that, how can any reasonable person still think that scientists are arrogant, cocksure know-it-alls? The scientific enterprise is arguably the most humbling experience one could have. Scientists get it wrong many, many times before they find the correct answers. And they’re constantly going over each other’s work with a magnifying glass, just hoping to find errors or unsubstantiated claims to gleefully point out. I’m no scientist, but I imagine that having one’s research subjected to such intense scrutiny by so many experts leaves little opportunity for inflated egos.

Notice that Pinker makes a value judgment when he writes that science is “a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge”, and that it’s not just the “particular methods or institutions of science but its value system” that give it its unique powers of discovery and illumination. Science is a moral undertaking. When people dedicate themselves to science, they are also declaring their commitment to moral values like honesty, humility and integrity. When they abandon any of these values, they cease doing science.

3.12.11

Coyne selects the following paragraph from Better Angels as a standout for the way it articulates Pinker’s views on science, which concur with Coyne’s.

(p. 181) Though we cannot logically prove anything about the physical world, we are entitled to have confidence in certain beliefs about it. The application of reason and observation to discover tentative generalizations about the world is what we call science. The progress of science with its dazzling success at explaining and manipulating the world, shows that knowledge of the universe is possible, albeit always probabilistic and subject to revision. Science is thus a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge—not the particular methods or institutions of science but its value system, namely to seek to explain the world, to evaluate candidate explanations objectively, and to be cognizant of the tentativeness and uncertainty of our understanding at any time.

After reading that, how can any reasonable person still think that scientists are arrogant, cocksure know-it-alls? The scientific enterprise is arguably the most humbling experience one could have. Scientists get it wrong many, many times before they find the correct answers. And they’re constantly going over each other’s work with a magnifying glass, just hoping to find errors or unsubstantiated claims to gleefully point out. I’m no scientist, but I imagine that having one’s research subjected to such intense scrutiny by so many experts leaves little opportunity for inflated egos.

Notice that Pinker makes a value judgment when he writes that science is “a paradigm for how we ought to gain knowledge”, and that it’s not just the “particular methods or institutions of science but its value system” that give it its unique powers of discovery and illumination. Science is a moral undertaking. When people dedicate themselves to science, they are also declaring their commitment to moral values like honesty, humility and integrity. When they abandon any of these values, they cease doing science.

3.12.11

29 November 2011

“All will have appetizing vaginas”

We’re all familiar with the promise of 72 virgins waiting in Paradise for devout Muslim men who martyr themselves in jihad against the enemies of Islam. But I recently came across a rather vivid description of said promise, written by Qur’anic commentator and polymath al-Suyuti (who died in 1505):

So Paradise is going to be full of guys strutting around with perpetual boners. I imagine that this being the afterlife, medical concerns regarding erections lasting longer than 4 hours are moot. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

Here we have a Saudi cleric, Muhammad al-Munajid, giving a lascivious description of the virginal delights awaiting good Muslim men when they shuffle off this mortal coil (and apparently only the men will have hot unvirgining sex to look forward to in Paradise).

If Al-Munajid’s Quranic exposition doesn’t make clear the misogyny and male chauvinism inherent in Islam, I don’t know what does. The women in Paradise are nothing more than the juvenile projections of selfish, immature boy-men who can’t stand the fact that women have flaws. It wouldn’t surprise me if this poisonous perfectionism contributes to the horrible treatment that women receive from a conservative Muslim patriarchy. Al-Munajid obviously finds certain natural aspects of women to be unseemly, if not outright disgusting.

Also, how is visible bone marrow supposed to be a turn-on? Or is that some Arab fetish I’m not aware of?

HT: Justin Griffith at Rock Beyond Belief

30.11.11

Each time we sleep with a houri we find her virgin. Besides, the penis of the Elected never softens. The erection is eternal; the sensation that you feel each time you make love is utterly delicious and out of this world and were you to experience it in this world you would faint. Each chosen one will marry seventy [sic] houris, besides the women he married on earth, and all will have appetizing vaginas.

So Paradise is going to be full of guys strutting around with perpetual boners. I imagine that this being the afterlife, medical concerns regarding erections lasting longer than 4 hours are moot. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

Here we have a Saudi cleric, Muhammad al-Munajid, giving a lascivious description of the virginal delights awaiting good Muslim men when they shuffle off this mortal coil (and apparently only the men will have hot unvirgining sex to look forward to in Paradise).

If Al-Munajid’s Quranic exposition doesn’t make clear the misogyny and male chauvinism inherent in Islam, I don’t know what does. The women in Paradise are nothing more than the juvenile projections of selfish, immature boy-men who can’t stand the fact that women have flaws. It wouldn’t surprise me if this poisonous perfectionism contributes to the horrible treatment that women receive from a conservative Muslim patriarchy. Al-Munajid obviously finds certain natural aspects of women to be unseemly, if not outright disgusting.

Also, how is visible bone marrow supposed to be a turn-on? Or is that some Arab fetish I’m not aware of?

HT: Justin Griffith at Rock Beyond Belief

30.11.11

24 November 2011

23 November 2011

A good rant from PZ Myers

Biology professor and popular blogger PZ Myers is one of the more outspoken public atheists, and a recent incident involving a gelato shop owner has roused Myers’s legendary ire. While I’m not completely sympathetic to his fierce and combative style, I do agree with many of the points he makes in his blog-post-cum-rant. Specifically, the charges he lays against those in the skeptic community who shy away from applying their vaunted skepticism and critical thinking to religion are spot on. Religious beliefs shouldn’t be exempt from the same level of scrutiny and evidential demands applied to UFO claims, conspiracy theories, psychic powers and Big Foot sightings.

I also agree with the spirit, if not the delivery, of Myers’s rant against ‘fair weather atheists’, which I take to mean atheists who adopt a holier-than-thou attitude towards their fellow unbelievers who are so vulgar as to noisily advocate for atheism. Knowing a few such fair weather atheists myself, I wonder if they realise that their freedom to not only not believe, but to also not have to fight for their right not to believe, is contingent on several factors: that they live in a mainly secular society, that they have been brought up in an environment conducive to tolerance of differing creeds and lifestyles, that they are protected by laws prohibiting discrimination against atheists or agnostics, that their social circle mostly consists of like-minded individuals who prevent them from feeling like they’re lonely islands of reason in an ocean of religious fervour.

It’s much harder to be a smug fair weather atheist when you’re an unbeliever in, say, Pakistan, or Iran, or the American Bible Belt. And the values that atheist advocates – from Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens to Myers, Greta Christina and Maryam Namazie – are standing up for are universal. They are fighting for the intellectual freedom and basic human rights of people everywhere, the sort of human goods that may be taken for granted by fair weather atheists, but most assuredly not by atheists who are harassed, persecuted, assaulted, killed or otherwise viciously discriminated against because they happen to be unbelievers in a society that hasn’t quite elevated snark and noncommittalism into a hip cultural institution.

24.11.11

I also agree with the spirit, if not the delivery, of Myers’s rant against ‘fair weather atheists’, which I take to mean atheists who adopt a holier-than-thou attitude towards their fellow unbelievers who are so vulgar as to noisily advocate for atheism. Knowing a few such fair weather atheists myself, I wonder if they realise that their freedom to not only not believe, but to also not have to fight for their right not to believe, is contingent on several factors: that they live in a mainly secular society, that they have been brought up in an environment conducive to tolerance of differing creeds and lifestyles, that they are protected by laws prohibiting discrimination against atheists or agnostics, that their social circle mostly consists of like-minded individuals who prevent them from feeling like they’re lonely islands of reason in an ocean of religious fervour.

It’s much harder to be a smug fair weather atheist when you’re an unbeliever in, say, Pakistan, or Iran, or the American Bible Belt. And the values that atheist advocates – from Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens to Myers, Greta Christina and Maryam Namazie – are standing up for are universal. They are fighting for the intellectual freedom and basic human rights of people everywhere, the sort of human goods that may be taken for granted by fair weather atheists, but most assuredly not by atheists who are harassed, persecuted, assaulted, killed or otherwise viciously discriminated against because they happen to be unbelievers in a society that hasn’t quite elevated snark and noncommittalism into a hip cultural institution.

24.11.11

07 November 2011

Mississippi redefines what it means to be a ‘person’ (and yes, God’s involved)

This is what happens when religidiocy butts into biology. A lump of undifferentiated cells suddenly becomes a person, and abortion and birth control become acts of murder.

From the New York Times:

The Mississippi amendment is the demon baby you’d expect from the unholy copulation of religiosity and scientific ignorance, as one doctor points out:

For those folks, Mississippian or otherwise, who think that a zygote is a person, here’s a picture to helpfully illustrate the error of your reasoning.

The Economist also covered this issue, with one reader, Benjamin Iwai of Missouri, writing a letter to the editor that displayed the merit of consistency vis-à-vis the idea of embryos being persons:

HT: Jerry Coyne

8.11.11

From the New York Times:

A constitutional amendment facing voters in Mississippi on Nov. 8, and similar initiatives brewing in half a dozen other states including Florida and Ohio, would declare a fertilized human egg to be a legal person, effectively branding abortion and some forms of birth control as murder. [...]

Many doctors and women’s health advocates say the proposals would cause a dangerous intrusion of criminal law into medical care, jeopardizing women’s rights and even their lives.

The amendment in Mississippi would ban virtually all abortions, including those resulting from rape or incest. It would bar some birth control methods, including IUDs and “morning-after pills,” which prevent fertilized eggs from implanting in the uterus. It would also outlaw the destruction of embryos created in laboratories.

The Mississippi amendment is the demon baby you’d expect from the unholy copulation of religiosity and scientific ignorance, as one doctor points out:

Dr. Randall S. Hines , a fertility specialist in Jackson working against Proposition 26 with the group Mississippians for Healthy Families, said that the amendment reflects “biological ignorance.” Most fertilized eggs, he said, do not implant in the uterus or develop further.

“Once you recognize that the majority of fertilized eggs don’t become people, then you recognize how absurd this amendment is,” Dr. Hines said. He fears severe unintended consequences for doctors and women dealing with ectopic or other dangerous pregnancies and for in vitro fertility treatments.

For those folks, Mississippian or otherwise, who think that a zygote is a person, here’s a picture to helpfully illustrate the error of your reasoning.

The Economist also covered this issue, with one reader, Benjamin Iwai of Missouri, writing a letter to the editor that displayed the merit of consistency vis-à-vis the idea of embryos being persons:

Sir, I was delighted to read your article about the effort in Mississippi to pass a state constitutional amendment to recognise embryos as people from the moment of fertilisation. My wife and I have been considering IVF to address our lack of success in conceiving a child. Mississippi’s proposed amendment gives us even more reason to pursue this treatment, and to move to Mississippi.

After the procedure we will insist on taking custody of any extra embryos that result from IVF – it is our right as parents after all. Once safely in our home we plan to keep them in a freezer in our basement and list them as child dependents for tax purposes, thus giving us a tax deduction. To protect the lives of our children in case of a power outage we will buy a backup generator. Anything less would be bad parenting.

HT: Jerry Coyne

8.11.11

Labels:

civil liberties,

ethics,

health,

human rights,

law,

politics,

religion,

science,

USA

06 November 2011

Thee-OH, Lo-JEE! What is it good for? Absolutely nuh-thing!

Ah, theology, a unique intellectual discipline where intelligent people write and talk intelligently about… nothing. Sure, they call this ‘nothing’ God, but it’s still nothing, since there’s no evidence that such a being not only exists, but exists in the manner or form that theologians conceive it to exist. Theology is a hollow exercise in hypothesis-making without any possible means to test those hypotheses. Theologians must be so lacking in self-awareness (or a functioning irony meter) that they can’t see the absurdity of trying to comprehend the supposedly incomprehensible. To explain the unexplainable. To say something about nothing.

A few weeks ago biology professor Jerry Coyne debated Catholic theologian John Haught at the University of Kentucky. The topic was a stomping ground of Coyne’s: are science and religion compatible? Unsurprisingly, Coyne’s rational, evidence-based arguments trumped Haught’s rhetorical obfuscation and unsupported claims. Post-debate, scandal erupted when Haught refused to allow the organisers to upload the video of the debate (he eventually relented after a justifiably severe public backlash, so you can watch the debate here, and the subsequent Q&A session here). Russell Blackford has given his thoughtful take on the Coyne-Haught drama.

A few weeks ago biology professor Jerry Coyne debated Catholic theologian John Haught at the University of Kentucky. The topic was a stomping ground of Coyne’s: are science and religion compatible? Unsurprisingly, Coyne’s rational, evidence-based arguments trumped Haught’s rhetorical obfuscation and unsupported claims. Post-debate, scandal erupted when Haught refused to allow the organisers to upload the video of the debate (he eventually relented after a justifiably severe public backlash, so you can watch the debate here, and the subsequent Q&A session here). Russell Blackford has given his thoughtful take on the Coyne-Haught drama.

03 November 2011

Science and politics (and how postmodernism can fuck things up)

Here’s the introduction for a New Scientist special report on the worrying state of science in the US (‘Decline and Fall’, 29 October):

Almost all the main Republican presidential candidates subscribe to some variety of anti-scientific bunkum. Michele Bachmann thinks science classes should teach creationism; Rick Perry rejects evolutionary theory because “it’s got some gaps in it”; Newt Gingrich considers embryonic stem cell research to be nothing less than murder; Herman Cain claims that people choose to be homosexual.

Meanwhile, Republican candidates who display a modicum of scientific literacy are practically committing political suicide. Shawn Lawrence Otto writes:

The US was founded on Enlightenment values and is the most powerful scientific nation on Earth. And yet the status of science in public life has never appeared to be so low.

As campaigning for the 2012 presidential election gets into full swing, US politics, especially on the right, appears to have entered a parallel universe where ignorance, denial and unreason trump facts, evidence and rationality.

Almost all the main Republican presidential candidates subscribe to some variety of anti-scientific bunkum. Michele Bachmann thinks science classes should teach creationism; Rick Perry rejects evolutionary theory because “it’s got some gaps in it”; Newt Gingrich considers embryonic stem cell research to be nothing less than murder; Herman Cain claims that people choose to be homosexual.

Meanwhile, Republican candidates who display a modicum of scientific literacy are practically committing political suicide. Shawn Lawrence Otto writes:

Republicans diverge from anti-science politics at their peril. When leading candidate Mitt Romney said: “I believe based on what I read that the world is getting warmer… humans contribute to that,” conservative radio commentator Rush Limbaugh responded with “Bye bye, nomination”. Romney back-pedalled, saying, “I don’t know if it’s mostly caused by humans.”

Labels:

Ben Goldacre,

culture,

history,

journalism,

media,

politics,

postmodernism,

reason,

science,

USA

19 October 2011

The story of an Indian atheist

The October 10 issue of The New Yorker has an article by Akash Kapur about an Indian cow broker named R. Ramadas (‘The Shandy’, online abstract here). Kapur writes about Ramadas’s line of work in the context of a rapidly modernising India. As expected of a New Yorker piece, Kapur’s journalism is engaging, eye-opening and full of pathos without being condescending or mawkish.

The article takes an unexpected turn when the reader discovers that Ramadas is an atheist. I say ‘unexpected’ because Ramadas is a poor, uneducated man born into the Dalit, or ‘untouchable’, caste of a highly religious and superstitious society. The trend is for religion to be more prevalent among those who share Ramadas’s demographic traits. Yet, amazingly, he bucks that trend.

Kapur writes:

The article takes an unexpected turn when the reader discovers that Ramadas is an atheist. I say ‘unexpected’ because Ramadas is a poor, uneducated man born into the Dalit, or ‘untouchable’, caste of a highly religious and superstitious society. The trend is for religion to be more prevalent among those who share Ramadas’s demographic traits. Yet, amazingly, he bucks that trend.

Kapur writes:

[Ramadas] said people always talked about gods and the miracles they’d supposedly performed. People believed the gods could heal a disease. But where was the proof? Ramadas believed only in what he could see. He believed in science. He believed in doctors and their injections.

18 October 2011

Religion: identity or idea?

Non-religious folks like me admittedly find it hard to understand how religious believers can get so emotionally invested in their beliefs. Any criticism or ridicule aimed at what is (to non-believers) obviously just a set of ideas no more sacred than any other set of ideas – whether political, cultural, philosophical – can often be taken as highly personal attacks by holders of those ideas. This conflation of ideas with identity allows believers to accuse religion’s critics of prejudice, even racism, when this is certainly not the case.

Greta Christina tackles this issue with her usual clarity and frankness. The following two paragraphs from her post describe both the nature of religious privilege and the outcome of denying religion that privilege.

Christina also has a few words of caution for ardent critics of sky-fairyism:

It may be trite advice, but if we critics of religion want to uphold the moral and intellectual integrity of our position, we would do well to bear these words in mind as we go about shooting down one lousy idea after another.

Happy hunting!

18.10.11

Greta Christina tackles this issue with her usual clarity and frankness. The following two paragraphs from her post describe both the nature of religious privilege and the outcome of denying religion that privilege.

A big part of what makes religion flourish is the special treatment it gets. The idea that religion is special and should be treated differently from other human ideas and activities is a ridiculously common one. It’s common to think that its leaders deserve special deference, that its holy places and relics should be treated with reverence, that people who are unusually religious must also be unusually virtuous, that it’s inherently rude or bigoted to criticize it. In the marketplace of ideas, religion gets a free ride. In an armored tank.

So criticizing religion doesn’t just have the effect of sometimes persuading people out of it. It also has the effect of repositioning religion as just another idea. It has the effect of treating religion the same way we treat ideas about politics, science, art, philosophy, medicine, ethics, social policy, etc. — namely, as fair game. Ideas that have to stand up on their own. Ideas that are only as good as the evidence and reason supporting them. Ideas that can be questioned and challenged and made fun of and blasted into shrapnel, just like any other. Criticizing religion doesn’t just expose religion as a singularly bad, entirely indefensible idea. It reframes it as an idea, period.

Christina also has a few words of caution for ardent critics of sky-fairyism:

I think that when we do hammer on the idea [of religion], we need to be very careful, and very rigorous, about hammering the idea without insulting the people.

We need to be very careful to say, “That idea makes no rational sense” — and not say, “You’re irrational.” We need to be very careful to say, “That idea is entirely divorced from reality” — and not say, “You are entirely divorced from reality.” We need to be very careful to say, “That’s a ridiculous and stupid idea” — and not say, “You are ridiculous and stupid.”

It may be trite advice, but if we critics of religion want to uphold the moral and intellectual integrity of our position, we would do well to bear these words in mind as we go about shooting down one lousy idea after another.

Happy hunting!

18.10.11

17 October 2011

Why (and how) science is incompatible with religion

Over at The Guardian, philosopher Julian Baggini explains why science and religion are oil and water, despite the intellectual acrobatics of theologians, religious scientists and ‘faithists’ (non-believers who nonetheless believe in the value of belief) defending accommodationism. Baggini’s article is a more eloquent version of my own arguments against the Gouldian concept of ‘non-overlapping magisteria’, or NOMA. I used the analogy of science and religion (supposedly) occupying two separate rooms but religion constantly intrudes into science’s room. Baggini expands on this illustration by showing how religion intrudes into the room it apparently has no business in entering, if the accommodationists are to be believed.

Accommodationists maintain that science is purely concerned with the ‘how’ questions, while religion deals with the ‘why’ questions. Both are compatible with each other so long as they stick to their respective spheres of expertise. But Baggini demonstrates that such claims are incorrect, even dishonest:

That’s the nub of this whole affair: religion assumes the necessity of agency, so all scientific ‘why’ questions that are agency-free will run afoul of religion, which sees itself as the only institution permitted to handle ‘why’ questions, questions that, from a religious perspective, inevitably have answers involving agency i.e. God. And by insisting on the ‘agency-why’ nature of agency-free questions, religion ends up trespassing into the domain of science, because ‘agency-why’ questions often turn into ‘how’ questions, which accommodationists assure us are the sole preserve of science. As Baggini points out:

Baggini exposes the falsehood of accommodationism’s premises: contrary to the NOMA ‘law’, religion keeps meddling in scientific matters because the strict separation that accommodationists believe exists actually doesn’t. Consequently, the myth of compatibility between science and religion is debunked; conflict between evidence-based understanding and faith is basically guaranteed when faith continually challenges the processes and findings of science.

So religion, by its inherent propensity for seeing agency in everything, including agency-free phenomena, cannot avoid interfering in the scientific enterprise because for religion, all ‘how’ questions are also ‘why’ questions. And the thing is, science also sees it that way, if in reverse – many ‘why’ questions are really ‘how’ questions. The key difference is that science doesn’t require agency to come up with answers. Religion always does.

Here’s an elegant graphic showing another way in which science and religion differ in their approach to finding answers to questions (click on the image to enlarge).

HT: Jerry Coyne

18.10.11

Accommodationists maintain that science is purely concerned with the ‘how’ questions, while religion deals with the ‘why’ questions. Both are compatible with each other so long as they stick to their respective spheres of expertise. But Baggini demonstrates that such claims are incorrect, even dishonest:

It sounds like a clear enough distinction, but maintaining it proves to be very difficult indeed. Many "why" questions are really "how" questions in disguise. For instance, if you ask: "Why does water boil at 100C?" what you are really asking is: "What are the processes that explain it has this boiling point?" – which is a question of how.

Critically, however, scientific "why" questions do not imply any agency – deliberate action – and hence no intention. We can ask why the dinosaurs died out, why smoking causes cancer and so on without implying any intentions. In the theistic context, however, "why" is usually what I call "agency-why": it's an explanation involving causation with intention.

So not only do the hows and whys get mixed up, religion can end up smuggling in a non-scientific agency-why where it doesn't belong.

That’s the nub of this whole affair: religion assumes the necessity of agency, so all scientific ‘why’ questions that are agency-free will run afoul of religion, which sees itself as the only institution permitted to handle ‘why’ questions, questions that, from a religious perspective, inevitably have answers involving agency i.e. God. And by insisting on the ‘agency-why’ nature of agency-free questions, religion ends up trespassing into the domain of science, because ‘agency-why’ questions often turn into ‘how’ questions, which accommodationists assure us are the sole preserve of science. As Baggini points out:

This means that if someone asks why things are as they are, what their meaning and purpose is, and puts God in the answer, they are almost inevitably going to make an at least implicit claim about the how: God has set things up in some way, or intervened in some way, to make sure that purpose is achieved or meaning realised. The neat division between scientific "how" and religious "why" questions therefore turns out to be unsustainable.

Baggini exposes the falsehood of accommodationism’s premises: contrary to the NOMA ‘law’, religion keeps meddling in scientific matters because the strict separation that accommodationists believe exists actually doesn’t. Consequently, the myth of compatibility between science and religion is debunked; conflict between evidence-based understanding and faith is basically guaranteed when faith continually challenges the processes and findings of science.

So religion, by its inherent propensity for seeing agency in everything, including agency-free phenomena, cannot avoid interfering in the scientific enterprise because for religion, all ‘how’ questions are also ‘why’ questions. And the thing is, science also sees it that way, if in reverse – many ‘why’ questions are really ‘how’ questions. The key difference is that science doesn’t require agency to come up with answers. Religion always does.

Here’s an elegant graphic showing another way in which science and religion differ in their approach to finding answers to questions (click on the image to enlarge).

HT: Jerry Coyne

18.10.11

12 October 2011

There should be more bookshops like this

Given the despondent bookstore scene in Melbourne, the arrival of Embiggen Books is glad news. Formerly based in Noosaville on the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, this independent bookstore packed up earlier this year for cooler climes southward, making its new home right in the Melbourne CBD (central business district).

But you know what’s more awesome, by orders of magnitude, than a mere indie bookstore? An indie bookstore that has “the biggest range of popular science titles in stock in the observable universe” and also sells scientific equipment and giftware, that deliberately refuses to sell books promoting pseudoscience, mysticism and irrational, baseless nonsense, and that is active in the skepticism movement.

An excerpt from the Embiggen Books website:

Imagine that, a bookshop with no self-proclaimed spiritual gurus, no anti-science screeds, no outright con jobs like The Secret, maybe even no section on religion (I haven’t visited the store yet). There will most likely be books on the history and philosophy of religion, perhaps of a comparative nature, but it would be wonderful to note an absence of books hawking one brand of sky-fairyism or another.

Fellow Melbournians who appreciate science, reason and skepticism, and books promoting them, while also having a sentimental fondness for brick-and-mortar bookstores are duly exhorted to pay Embiggen Books a visit, and support them with your custom. You can also buy books online and have them delivered to you, so even non-Melbournians can support a business dedicated to science, reason and skepticism.

The address and contact number for Embiggen Books:

197-203 Little Lonsdale St, Melbourne, 3000

Phone: (03) 9662 2062

HT: Russell Blackford

13.10.11

But you know what’s more awesome, by orders of magnitude, than a mere indie bookstore? An indie bookstore that has “the biggest range of popular science titles in stock in the observable universe” and also sells scientific equipment and giftware, that deliberately refuses to sell books promoting pseudoscience, mysticism and irrational, baseless nonsense, and that is active in the skepticism movement.

An excerpt from the Embiggen Books website:

[The bookshop’s] parents Mr and Mrs Embiggen have had long interests in evidence based understanding, reason and life, the universe and everything. They have sieved out pseudoscience wherever they smell it so you won’t find new age malarkey in the stock list.

Imagine that, a bookshop with no self-proclaimed spiritual gurus, no anti-science screeds, no outright con jobs like The Secret, maybe even no section on religion (I haven’t visited the store yet). There will most likely be books on the history and philosophy of religion, perhaps of a comparative nature, but it would be wonderful to note an absence of books hawking one brand of sky-fairyism or another.

Fellow Melbournians who appreciate science, reason and skepticism, and books promoting them, while also having a sentimental fondness for brick-and-mortar bookstores are duly exhorted to pay Embiggen Books a visit, and support them with your custom. You can also buy books online and have them delivered to you, so even non-Melbournians can support a business dedicated to science, reason and skepticism.

The address and contact number for Embiggen Books:

197-203 Little Lonsdale St, Melbourne, 3000

Phone: (03) 9662 2062

HT: Russell Blackford

13.10.11

11 October 2011

Hitchens recommends books to a young, bright girl

Christopher Hitchens recently attended the Atheist Alliance of America convention in Houston, Texas. Over at Why Evolution Is True, Jerry Coyne has uploaded videos of Hitchens receiving the Richard Dawkins Award for promoting freethought and atheism, and holding forth on Rick Perry and Mormonism.

A highlight of the event was Hitchens taking the time to have a one-on-one chat with 8-year-old Mason Crumpacker. During the Q&A session Mason had asked Hitchens what books he thought she should read in order to become a freethinker like him. Hitchens graciously offered to see Mason afterwards to give her his recommendations.

Coyne has a post on the exchange between Hitchens and Mason written by Mason’s mum Anne, who accompanied her daughter. It was a beautiful moment, when one of the most keen and erudite minds alive today passed on a precious fragment of his mental library to a young, precocious girl who hoped to follow in his footsteps. A dying man planted seeds of knowledge and wisdom in the mind of a potential successor.

Mason wrote a lovely thank you letter to Hitchens:

Dear Mr. Hitchens,

Thank you for your kindness to me and all of the wonderful books you recommended to help me think for myself. Thank you also for taking my question very seriously. When I was talking to you I felt important because you treated me like a grown up. I feel very fortunate to have met you. I think more children should read books. I also think that all adults should be honest to children like you to me. For the rest of my life I will remember and cherish our meeting and will try to continue to ask questions.

Sincerely,

Mason

P.S. I would like to start with “The Myths” by Robert Graves.

Anne Crumpacker captures that fateful meeting between Hitchens and Mason with heartbreaking poignancy:

I’m not a professional writer, just a mom, but if I get to make only one comment it would be this: There isn’t a magic reading list. Never was. Never will be. The reason what transpired that night was memorable was the wondrous Socratic feel of the exchange. Here was a man, a great thinker of our time who has spent his life developing and honing his intellect, challenging the next generation to pick up the mantle. What all these books have in common is they demand us to question, search and engage. They don’t preach, patronize or indoctrinate. They are a joyful expression of the whole of the human experience. The very best examples of a life fully lived.

We are about to lose a giant among us, but we, as atheists know there can be no greater Valhalla then to join the great conversation of the philosophers. We can honor Christopher Hitchens’ life by teaching our children his best virtues: to study broadly, to laugh heartily, to fight ardently, and to question relentlessly. Books are timeless companions and friends. Mason will surely spend her life in the company of illustrious authors gone before. Naturally, she was introduced to many of them that night by a kind man, with flashing eyes, sitting at a table who is about to join their company.

11.10.11

10 October 2011

Alt-med woo peddlers aren’t happy that their bullshit is being exposed

The James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) has an article on their website about the frustration of ‘alternative’ medicine woomongers in the UK over having their lies and misinformation being exposed by skeptics, with help from the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). Looks like the alt-med crowd is feeling the impact of awareness-raising campaigns run by skeptic activists; alt-med’s often baseless claims regarding the efficacy of its treatments and products are being publicly challenged, and independent regulators like the ASA are lending their muscle to the skeptic cause.

Referring to real doctors and skeptics, this statement from the pro-alt-med website ASA Sucks (how mature) clearly indicates alt-med’s disdain for scientific rigour in determining the efficacy of medical treatments:

Far from being an “ill-founded belief”, double blind placebo trials are essential to prevent subject and tester bias from compromising the objectivity of the trial. Using this method is definitely a sign that good science is being done. Alt-med folks understandably dislike double blind placebo trials because they all too often produce results that do not confirm alt-med claims. Since they are emotionally invested in their anti-conventional medicine ideology, alt-med folks blame the double blind placebo method for the failure of their ‘theories’, rather than the inherent flaws of their ideology.

Concerning the ASA Sucks website, Tim Farley, who wrote the JREF article, makes the following observations:

The people behind ASA Sucks can’t be very convinced of the righteousness of their cause if they haven’t got the integrity to back up their accusations with their names.

In the immortal words of Tim Minchin:

10.10.11

Referring to real doctors and skeptics, this statement from the pro-alt-med website ASA Sucks (how mature) clearly indicates alt-med’s disdain for scientific rigour in determining the efficacy of medical treatments:

Their reason for hating complementary medicine is based on the ill-founded belief that double blind placebo based trials are good science.

Far from being an “ill-founded belief”, double blind placebo trials are essential to prevent subject and tester bias from compromising the objectivity of the trial. Using this method is definitely a sign that good science is being done. Alt-med folks understandably dislike double blind placebo trials because they all too often produce results that do not confirm alt-med claims. Since they are emotionally invested in their anti-conventional medicine ideology, alt-med folks blame the double blind placebo method for the failure of their ‘theories’, rather than the inherent flaws of their ideology.

Concerning the ASA Sucks website, Tim Farley, who wrote the JREF article, makes the following observations:

In a pattern we’ve seen before, the complaint site does not stick to factual debate, but delves deep into logical fallacies, conspiracy theory thinking and other canards. It makes rude comments about Simon Singh and others, but somehow manages to miss the fact (clearly published on the [skeptic organisation] Nightingale Collaboration website) that the group is actually run by [Alan] Henness and [Maria] MacLachlan.

Meanwhile the complaint site itself was registered anonymously Monday through a U.S. company and is hosted on servers in Malaysia. None of the text on the site is signed, there’s no indication of who is behind this effort. Whoever is behind it is not only angry, but anxious to not be publicly known. (Compare this with the skeptics, who are very open about what they are doing, and even have posted a code of conduct).

The people behind ASA Sucks can’t be very convinced of the righteousness of their cause if they haven’t got the integrity to back up their accusations with their names.

In the immortal words of Tim Minchin:

Do you know what they call “alternative medicine” that’s been proved to work? Medicine.

10.10.11

06 October 2011

Steven Pinker’s new book

Human beings are becoming less and less violent. This is the premise of renowned psychologist Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels Of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.

Pinker is considered to be one of the finest science writers of our time, with a gift for making complex ideas accessible to the layperson in his typically lucid yet highly informative writing style. His book on human language, The Language Instinct (1994), is a science classic. Reading The Blank Slate (2002) was a milestone in my intellectual journey. Pinker’s arguments against the tabula rasa theories of the social sciences left an indelible impression on me, and he convincingly demolished the ‘noble savage’ and ‘ghost in the machine’ ideas so widely held. I’m looking forward to reading his latest work for a similarly illuminating experience.

John Horgan has written a mostly positive review of Better Angels. Sam Harris interviewed Pinker and posted the result on his blog. I especially liked Pinker’s response when Harris raised the issue of so-called ‘atheist’ atrocities (obviously a dig at a common, and incorrect, anti-atheism argument):

Pinker is considered to be one of the finest science writers of our time, with a gift for making complex ideas accessible to the layperson in his typically lucid yet highly informative writing style. His book on human language, The Language Instinct (1994), is a science classic. Reading The Blank Slate (2002) was a milestone in my intellectual journey. Pinker’s arguments against the tabula rasa theories of the social sciences left an indelible impression on me, and he convincingly demolished the ‘noble savage’ and ‘ghost in the machine’ ideas so widely held. I’m looking forward to reading his latest work for a similarly illuminating experience.

John Horgan has written a mostly positive review of Better Angels. Sam Harris interviewed Pinker and posted the result on his blog. I especially liked Pinker’s response when Harris raised the issue of so-called ‘atheist’ atrocities (obviously a dig at a common, and incorrect, anti-atheism argument):

05 October 2011

Possibly the BEST description of the Bible

Biology professor Jerry Coyne is garnering a reputation for his public criticism of religion in general and accommodationism in particular (the Templeton Foundation is his arch-nemesis). Of course, this means that Coyne now attracts the attention of god-botherers who have had their pious sensibilities bruised by his arguments. Not that the good professor minds the (perhaps unintentional) publicity his opponents generate for him.

The latest sky-fairyist to take a snipe at Coyne is New York Times columnist Ross Douthat. Being a Catholic, Douthat takes issue with Coyne’s blog post eviscerating the Christian doctrine of Adam and Eve being the first humans and thus the progenitors of us all. But Coyne’s scientific debunking of that myth wasn’t what made Douthat go “tsk tsk”. No, what Douthat objected to was Coyne’s inability to see the Adam and Eve story as a metaphor. It’s supposed to be viewed through the lens of ‘sophisticated theology’, not taken literally! Simplistic atheists like Coyne misrepresent the subtleties of Christianity by painting all believers as Biblical literalists, Douthat squawks. To these protestations, Coyne responds:

Indeed, how do religionists know which bits of their sacred texts are to be taken as fact and which are to be read as metaphor? Could it be that they don’t actually have an objective method to make that discrimination? That they just make up the rules as they go along?

Fallible readers of supposedly infallible books are necessarily going to come up with faulty, inconsistent, contradictory interpretations. Coyne gives the best description of the Bible that I’ve ever come across. It’s accurate, fair, and unsparing.

6.10.11

The latest sky-fairyist to take a snipe at Coyne is New York Times columnist Ross Douthat. Being a Catholic, Douthat takes issue with Coyne’s blog post eviscerating the Christian doctrine of Adam and Eve being the first humans and thus the progenitors of us all. But Coyne’s scientific debunking of that myth wasn’t what made Douthat go “tsk tsk”. No, what Douthat objected to was Coyne’s inability to see the Adam and Eve story as a metaphor. It’s supposed to be viewed through the lens of ‘sophisticated theology’, not taken literally! Simplistic atheists like Coyne misrepresent the subtleties of Christianity by painting all believers as Biblical literalists, Douthat squawks. To these protestations, Coyne responds:

I don’t insist on a view of “true” religion as a literal reading of scripture, whether it be the Bible, the Qur’an, or any other holy book. What I insist on is that those people who see some parts of scripture as metaphor, and others as true, kindly inform us how they know the difference.

Indeed, how do religionists know which bits of their sacred texts are to be taken as fact and which are to be read as metaphor? Could it be that they don’t actually have an objective method to make that discrimination? That they just make up the rules as they go along?

|

| Religion: the original Calvinball |

Fallible readers of supposedly infallible books are necessarily going to come up with faulty, inconsistent, contradictory interpretations. Coyne gives the best description of the Bible that I’ve ever come across. It’s accurate, fair, and unsparing.

The Bible is a jerry-rigged, sloppily-edited, largely fabricated, and palpably incomplete collection of oral traditions and myths, once intended to be the best explanation for the origins of our species, but now to be regarded merely as a quaint and occasionally enjoyable origin fable related by ignorant and relatively isolated primitive ancestors. It’s a palimpsest that is largely fictional, a story reworked many times, but based on our ancestors’ best understanding of how we came about. It’s simply a myth, no truer than the many myths, religious or otherwise, that preceded it. Embedded in it are some good moral lessons, but also many bad moral lessons. And the “good” morality doesn’t come from God, but was simply worked into the fairy tale by those who adhered to that morality for secular reasons.

6.10.11

When women betray their own gender

Here’s the gist of Madeleine Bunting’s Guardian article: Western imperialists cynically used the oppression of women by the Taliban as a pretext to carry out the US-led Afghan War.

Bunting isn’t anti-women’s rights; she’s anti-fighting-for-women’s-rights-while-also-shooting-and-bombing-their-oppressors. Now this may seem like a fair enough position to take. Spreading the idea of gender equality shouldn’t require the invasion of another country and subsequent mass killing of its people. Yet Bunting affects a concerned pacifism that disturbingly slips into cultural relativism.

Regarding the initial enthusiasm for the Afghan War, she writes:

Key to this largely supportive public opinion was how, over the course of a few weeks in 2001, a war of revenge was reframed as a war for human rights in Afghanistan, and in particular the rights of women. It was a narrative to justify war that proved remarkably powerful. A cause that had been dismissed and ignored for years in Washington suddenly moved centre-stage. The video of a woman being executed in Kabul stadium that the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan had offered to the BBC and CNN without success was taken up by the Pentagon and used extensively. The Taliban's brutal treatment of women, the closure of girls schools: all were used to justify military invasion and close down debate.

04 October 2011

Warren vs Rand

Massachusetts Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren is the antithesis of Ayn Rand, the writer and founder of Objectivism. Two months ago Warren gave a speech that was essentially a rebuttal to Rand’s philosophical ideas concerning the rights of the individual versus the rights of the society in which an individual lives.

Rand notoriously rejected the idea that society, i.e. the state, had a rightful claim to a share of the fruits of an individual’s labour, i.e. taxes. Rand believed that taxation was a form of theft, since it involves the use of force or coercion by the state to take people’s money without requiring their consent. However, since governments require revenue in order to function, Rand conceded that taxes were necessary but insisted that they should be voluntary, and only collected to fund the most basic services that the state could rightfully be expected to provide: the police, the military, and the law courts.

In a fully free society, taxation—or, to be exact, payment for governmental services—would be voluntary. Since the proper services of a government—the police, the armed forces, the law courts—are demonstrably needed by individual citizens and affect their interests directly, the citizens would (and should) be willing to pay for such services, as they pay for insurance. […]

The principle of voluntary government financing rests on the following premises: that the government is not the owner of the citizens’ income and, therefore, cannot hold a blank check on that income—that the nature of the proper governmental services must be constitutionally defined and delimited, leaving the government no power to enlarge the scope of its services at its own arbitrary discretion. Consequently, the principle of voluntary government financing regards the government as the servant, not the ruler, of the citizens—as an agent who must be paid for his services, not as a benefactor whose services are gratuitous, who dispenses something for nothing.

Labels:

Ayn Rand,

books,

capitalism,

ethics,

philosophy,

politics,

USA

29 September 2011

Happy Blasphemy Day!

Blasphemy is an epithet bestowed by superstition upon common sense.

- Robert Green Ingersoll

Today is International Blasphemy Rights Day. It’s an appropriate occasion to reflect on one basic human right many of us take for granted: freedom of expression. Many countries, particularly those with Muslim majorities or theocracies, have laws against insulting or criticising religion. Punishments for transgressing such laws include fines, jail, and the death penalty. Apart from these legal, state-sanctioned punishments, there’s also the informal consequences of social condemnation, ostracism and physical violence inflicted upon those who overtly disrespect religion.

Blasphemy laws have been used to silence and intimidate those who dare to challenge religion’s self-awarded exemption from criticism and mockery. Mortal, fallible men (and they are almost always men) pretend that they are defending the sacredness of their God by creating laws punishing those who slander him, but what they are really doing is imposing their own temporal authority on others. As the 19th century American humanist orator and outspoken critic of religion Robert Green Ingersoll observed:

An infinite God ought to be able to protect himself, without going in partnership with State Legislatures. Certainly he ought not so to act that laws become necessary to keep him from being laughed at. No one thinks of protecting Shakespeare from ridicule, by the threat of fine and imprisonment.

Let’s be clear about the purpose of Blasphemy Rights Day – it’s not an excuse to be a dick just for kicks. As the good folks at the Center for Inquiry explain:

The goal is not to promote hate or violence. While many perceive blasphemy as insulting and offensive, it isn't about getting enjoyment out of ridiculing and insulting others. The day was created as a reaction against those who would seek to take away the right to satirize and criticize a particular set of beliefs given a privileged status over other beliefs. Criticism and dissent towards opposing views is the only way in which any nation with any modicum of freedom can exist.

If we can make fun of people’s political, philosophical or cultural convictions, we should be free to do the same for their religious ones. Religionists who demand that their beliefs be treated as an exceptional case are like so many naked emperors demanding that their non-existent raiment be unquestioningly admired. But they’re starkers, and blasphemers are simply pointing that out.

30.9.11

27 September 2011

The end of print?

Sam Harris’s latest blog post spells out in brow-furrowing, lip-chewing detail the gloomy future of the printed book. Fellow bibliophiles are going to find it a depressing read. I do.

Martin at Furious Purpose has commented on the rather dire Melbourne bookshop scene. Borders and Angus & Robertson are gone. My regular supplier of ink-on-dead-trees, Reader’s Feast, is now a famine – they shut shop a few months ago. The only bookstore left that is likely to stock the kind of books I’m willing to pay grossly inflated prices for (thanks Australian government! /sarcasm) is Readings in Carlton. If (when?) that place shutters, I’m going to need therapy.

In this digital, Amazonian age we currently inhabit, book lovers need to somehow make the printed word indispensable, hip even. John Waters has an idea on how to do just that.

HT: Martin

28.9.11

Martin at Furious Purpose has commented on the rather dire Melbourne bookshop scene. Borders and Angus & Robertson are gone. My regular supplier of ink-on-dead-trees, Reader’s Feast, is now a famine – they shut shop a few months ago. The only bookstore left that is likely to stock the kind of books I’m willing to pay grossly inflated prices for (thanks Australian government! /sarcasm) is Readings in Carlton. If (when?) that place shutters, I’m going to need therapy.

In this digital, Amazonian age we currently inhabit, book lovers need to somehow make the printed word indispensable, hip even. John Waters has an idea on how to do just that.

HT: Martin

28.9.11

Blackford on how religion disparages the good things in life

Earlier this month Russell Blackford participated in a debate organised by Intelligence Squared Australia, with the motion ‘Atheists are wrong’. Blackford along with Jane Caro and Tamas Pataki made up the ‘against’ team, which won the debate (insert smug smile here). In a recent blog post, Blackford comments on how the debate arguments of Tracey Rowland – who was for the motion – reflect a common characteristic of religion: its propensity to “[do] dirt on everything good in life”. Whether it’s social relationships, politics, trade or sex, religion preaches that without God, these things lose their value, or become corrupted. As Rowland, informed by her Catholicism, sees it:

Blackford disagrees. The presence or absence of a supernatural divinity is irrelevant to the goodness or badness of things like politics or sex. In fact, the religionist insistence that their goodness depends on the existence of a supernatural divinity belittles their inherent worth, as Blackford argues:

The sort of ridiculous, unsubstantiated claims made by Rowland and her sky-fairyist ilk are rooted in the same emotive soil that feeds anti-scientific criticisms accusing science of ‘disenchanting’ the world. According to its detractors, science sucks the fuzzy-wuzzy, warm gooey caramel centre out of things like love, beauty and ‘spirituality’ (an ambiguous term) with its cold, unromantic, materialist ideology. What tosh. If any ideology is sucking the life-affirming goodness out of human preoccupations, it’s religion, with its perverse delight in seeing corruption, shame and taint in what are actually natural, pleasurable and even beneficial aspects of our humanity.

Blackford rightly asserts that “the religious mind thinks little of human pleasure and desire, and so disparages ordinary kinds of goodness.”

Quite so.

27.9.11

Sexual relations hollowed out into their materialist shell become mutual manipulation; political relations hollowed out into their materialist shell become brutal power; and market relations hollowed out into their material shell give us consumerism and status anxiety.

Blackford disagrees. The presence or absence of a supernatural divinity is irrelevant to the goodness or badness of things like politics or sex. In fact, the religionist insistence that their goodness depends on the existence of a supernatural divinity belittles their inherent worth, as Blackford argues:

Religionists cannot explain how the supernatural makes things that are not otherwise good become so, or how good things are any less so in the absence of some sort of supernatural power. No one has ever shown how that is a coherent way of thinking about the issues. If something has the properties that are required to satisfy certain human needs, desires, interests, etc., then we are quite entitled to judge it as "good" ... whether a supernatural power, such as God, exists or not.

The sort of ridiculous, unsubstantiated claims made by Rowland and her sky-fairyist ilk are rooted in the same emotive soil that feeds anti-scientific criticisms accusing science of ‘disenchanting’ the world. According to its detractors, science sucks the fuzzy-wuzzy, warm gooey caramel centre out of things like love, beauty and ‘spirituality’ (an ambiguous term) with its cold, unromantic, materialist ideology. What tosh. If any ideology is sucking the life-affirming goodness out of human preoccupations, it’s religion, with its perverse delight in seeing corruption, shame and taint in what are actually natural, pleasurable and even beneficial aspects of our humanity.

Blackford rightly asserts that “the religious mind thinks little of human pleasure and desire, and so disparages ordinary kinds of goodness.”

Religion is not the root of all evil, but it is far from being the source of ordinary goodness in our lives. On the contrary, it is an enemy of ordinary goodness. We can lead good and fruitful lives without God or any belief in the supernatural, and that's what I suggest we all do. Life without God is not thereby way diminished or hollowed out. That's an unsustainable claim. It is pathological to think of the world that way.

Quite so.

27.9.11

22 September 2011

More from Christina on fashion (and its frustrations)

It seems that Greta Christina’s previous posts on fashion rubbed some of her readers the wrong way. She felt compelled to address this pushback with another post, where she clarifies her original argument that fashion is a form of communication, whether one is conscious of it or not.

Judging by the raw nerves this subject matter has touched, one thing fashion definitely isn’t is irrelevant. Love it, hate it, apathetic about it – so long as we homo sapiens are subject to both the physical necessity of clothing our bodies and the psychological occupations of our inner lives (status anxieties, moral values, sexual attraction, aesthetic appreciation, emotional needs and cognitive biases), we will inevitably have some kind of relationship to fashion.

I sympathise with Christina’s position, yet I also understand why her views have caused offence. Still, she’s trying to meet her dissenters halfway by acknowledging their grievances against either her arguments or fashion itself. But people being people, I doubt that the controversy surrounding anything fashion related will be tidily resolved by Christina’s latest essay.

23.9.11

Judging by the raw nerves this subject matter has touched, one thing fashion definitely isn’t is irrelevant. Love it, hate it, apathetic about it – so long as we homo sapiens are subject to both the physical necessity of clothing our bodies and the psychological occupations of our inner lives (status anxieties, moral values, sexual attraction, aesthetic appreciation, emotional needs and cognitive biases), we will inevitably have some kind of relationship to fashion.

I sympathise with Christina’s position, yet I also understand why her views have caused offence. Still, she’s trying to meet her dissenters halfway by acknowledging their grievances against either her arguments or fashion itself. But people being people, I doubt that the controversy surrounding anything fashion related will be tidily resolved by Christina’s latest essay.

23.9.11

21 September 2011

“It’s not the coolness of atheism. It’s the lameness of religion.”

Anglican archbishop Rowan Williams thinks that religion (i.e. Williams’s own Jesus-centric brand of it) is losing the popularity contest to atheism because godlessness is perceived to be ‘cool’. The presumably uncool archbishop opines: